In a region where rain is rare and water more precious than oil, the United Arab Emirates once had its sights set on an audacious engineering marvel: towing a gigantic Antarctic iceberg to its sun-baked coast to quench thirst, summon clouds, and maybe even reshape climate patterns. But as of 2025, the only glacier ice that has made it to Dubai is not floating off the coast but chilling highball glasses in rooftop bars, courtesy of a boutique Greenland startup.

The UAE Iceberg Project : Cold Ambitions in a Hot Desert

Launched in 2017 by the National Advisor Bureau Limited , a private Abu Dhabi-based company, the UAE Iceberg Project sought to tow a massive tabular iceberg, measuring roughly 2 kilometers long by 500 meters wide, from Antarctica to Fujairah, a coastal emirate on the Gulf of Oman.

The logic, according to Abdulla Alshehi , the firm’s managing director and the project’s chief architect, was straightforward: an average iceberg holds over 20 billion gallons of fresh water, enough to supply 1 million people for five years. “This is the purest water in the world,” he told Gulf News in 2017. And the UAE, consuming 15% of the world’s desalinated water and facing depleting groundwater within 15 years, was in no position to ignore unconventional ideas.

The iceberg, selected via satellite near Heard Island in the Southern Ocean, would undertake a 12,000-kilometer (≈6,480 nautical miles), 10-month journey across the Southern, Indian, and Arabian Seas to reach the coast of Fujairah in the UAE. Towed by large ocean-going vessels, it would travel northward through the Indian Ocean before entering the Gulf of Oman.

Upon arrival, it would be stationed roughly 3 kilometers off Fujairah’s coast. Harvesting would begin immediately, with the aim of extracting potable water within two to three months before significant melting occurs. Computer simulations commissioned by the company projected that up to 30% of the iceberg’s mass could be lost during the journey, a challenge the team hopes to mitigate by timing its arrival during the UAE’s winter season, when sea temperatures are lower and melting would slow.

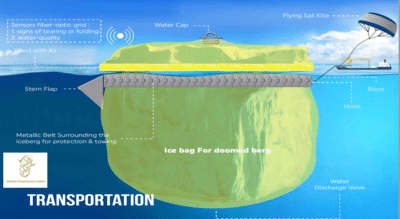

To prevent breakup during the long journey, Alshehi’s firm developed a patent-pending metal belt, a kind of reinforced corset designed to hold the iceberg intact against wave stress and temperature gradients. In 2020, the UK Intellectual Property Office granted Alshehi a patent for his invention, called the " Iceberg Reservoirs " system. The patent was promoted as a credibility boost to attract investment and reinforce the project's technical feasibility.

A pilot project, costed between $60–80 million, was announced for 2019. A smaller iceberg was to be towed to Cape Town or Perth as proof of concept. The full UAE project carried a price tag of $100–150 million.

Despite a splashy website launch (www.icebergs.world), promises of scientific panels, and a vision of global humanitarian water relief, no trial was ever confirmed to have taken place. As of 2025, there’s been no operational progress, no updated logistics, and no official cancellation, just prolonged silence.

The Rainmaker Fantasy

What made the proposal especially memorable was its near-mystical secondary goal: climate engineering. Alshehi claimed that the presence of a colossal iceberg floating off the UAE coast could induce localized weather changes.

“Cold air gushing from an iceberg close to the Arabian Sea would cause a trough and rainstorms,” he told local media. The iceberg, he argued, could “create a vortex” that would attract clouds from across the region, generating year-round rain for the desert interior. This, he claimed, could help reverse desertification and transform arid landscapes into lush, green areas, with benefits for agriculture, biodiversity, and the broader ecosystem.

Meteorologists weren’t sold. While some acknowledged localized effects, like minor cloud formation due to temperature differentials, experts like Linda Lam from Weather.com said sustained, regional rainstorms were unlikely due to the complex nature of atmospheric dynamics.

Water Crisis and the Case for Desperation

The UAE’s acute water issues form the bedrock of the project’s rationale. The country experiences a paltry 120 millimeters of rainfall annually, and according to a 2015 Associated Press report, its groundwater could be fully depleted within 15 years. Meanwhile, the Gulf states have among the highest water usage rates in the world: around 500 liters per person per day.

Desalination, though critical, is energy-intensive, costly, and environmentally damaging. Alshehi warned of desalination plants pumping concentrated brine back into the Gulf, increasing salinity and harming marine life. His iceberg initiative, he claimed, would be not only cheaper in the long run but eco-friendlier, despite concerns about dragging a 100,000-year-old ice mass across the globe.

He asserted that environmental impact assessments had been conducted, and results suggested minimal disruption to ecosystems,though no independent third-party review was ever published.

Ice, Reimagined: A Greenland Startup Finds the Sweet Spot

While Alshehi’s Antarctic ambitions appear stalled in bureaucratic limbo, a smaller, scrappier company in Greenland has quietly realized a modest version of his vision,not as a humanitarian water source, but as luxury indulgence.

Founded in 2022 by Greenlandic entrepreneurs, Arctic Ice ships ice harvested from Greenland’s fjords to high-end bars and restaurants in Dubai. Their first commercial shipment, around 22 metric tonnes, arrived recently, offering the “cleanest H₂O on Earth” to be shaved into ice cubes for cocktails, ice baths, and facial massages in Dubai’s spas.

The process is artisanal: Using a crane-equipped boat, workers collect naturally calved icebergs from the Nuup Kangerlua fjord near Nuuk. Only the clearest, bubble-free ice, locally known as “black ice,” is selected. These are believed to be over 100,000 years old, having never touched soil or contaminants.

Each chunk is cut with sanitized chainsaws, stored in food-grade insulated crates, and sampled for lab analysis to screen for ancient microorganisms or harmful bacteria. The ice is shipped via refrigerated containers aboard cargo ships already returning empty from Greenland, minimizing additional emissions. The second leg, from Denmark to Dubai, completes the frozen supply chain.

Despite the company’s carbon-neutral commitment, backlash has been fierce. Critics online lambast the concept as “climate dystopia,” arguing that glacial ice should not be commodified, especially given the accelerating melt of the Greenland Ice Sheet. Co-founder Malik V. Rasmussen says some messages have verged on death threats.

Still, Arctic Ice insists it is creating economic opportunity for a financially dependent Greenland, where 55% of the budget is subsidized by Denmark. “We make all our money from fish and tourism,” Rasmussen said. “I’ve always wanted to find something else we can profit from.”

The Fine Line Between Innovation and Spectacle

Both projects,the giant iceberg tow from Antarctica and the boutique glacier cubes from Greenland, highlight a pressing tension: how far will humanity go to secure water, and at what cost?

Alshehi’s vision is bold but fraught with logistical and ethical challenges. Icebergs aren’t endlessly renewable, and towing them across hemispheres feels more sci-fi than sustainable.

Arctic Ice’s venture, meanwhile, has found a controversial niche,combining novelty, luxury, and symbolism. In a time of climate anxiety, it offers an icy illusion of control, frozen fragments of a melting world, crafted into cocktail spheres.

Whether climate solution or spectacle, these ideas raise key questions: Who owns natural ice? Can it be harvested responsibly? And as water scarcity grows, how do we balance local needs with global care?

For now, the UAE’s giant iceberg remains a dream deferred, and Dubai’s cocktails are as cold as ever, just sourced from a little farther north, and in smaller, sparkling doses.

The UAE Iceberg Project : Cold Ambitions in a Hot Desert

Launched in 2017 by the National Advisor Bureau Limited , a private Abu Dhabi-based company, the UAE Iceberg Project sought to tow a massive tabular iceberg, measuring roughly 2 kilometers long by 500 meters wide, from Antarctica to Fujairah, a coastal emirate on the Gulf of Oman.

The logic, according to Abdulla Alshehi , the firm’s managing director and the project’s chief architect, was straightforward: an average iceberg holds over 20 billion gallons of fresh water, enough to supply 1 million people for five years. “This is the purest water in the world,” he told Gulf News in 2017. And the UAE, consuming 15% of the world’s desalinated water and facing depleting groundwater within 15 years, was in no position to ignore unconventional ideas.

The iceberg, selected via satellite near Heard Island in the Southern Ocean, would undertake a 12,000-kilometer (≈6,480 nautical miles), 10-month journey across the Southern, Indian, and Arabian Seas to reach the coast of Fujairah in the UAE. Towed by large ocean-going vessels, it would travel northward through the Indian Ocean before entering the Gulf of Oman.

Upon arrival, it would be stationed roughly 3 kilometers off Fujairah’s coast. Harvesting would begin immediately, with the aim of extracting potable water within two to three months before significant melting occurs. Computer simulations commissioned by the company projected that up to 30% of the iceberg’s mass could be lost during the journey, a challenge the team hopes to mitigate by timing its arrival during the UAE’s winter season, when sea temperatures are lower and melting would slow.

To prevent breakup during the long journey, Alshehi’s firm developed a patent-pending metal belt, a kind of reinforced corset designed to hold the iceberg intact against wave stress and temperature gradients. In 2020, the UK Intellectual Property Office granted Alshehi a patent for his invention, called the " Iceberg Reservoirs " system. The patent was promoted as a credibility boost to attract investment and reinforce the project's technical feasibility.

A pilot project, costed between $60–80 million, was announced for 2019. A smaller iceberg was to be towed to Cape Town or Perth as proof of concept. The full UAE project carried a price tag of $100–150 million.

Despite a splashy website launch (www.icebergs.world), promises of scientific panels, and a vision of global humanitarian water relief, no trial was ever confirmed to have taken place. As of 2025, there’s been no operational progress, no updated logistics, and no official cancellation, just prolonged silence.

The Rainmaker Fantasy

What made the proposal especially memorable was its near-mystical secondary goal: climate engineering. Alshehi claimed that the presence of a colossal iceberg floating off the UAE coast could induce localized weather changes.

“Cold air gushing from an iceberg close to the Arabian Sea would cause a trough and rainstorms,” he told local media. The iceberg, he argued, could “create a vortex” that would attract clouds from across the region, generating year-round rain for the desert interior. This, he claimed, could help reverse desertification and transform arid landscapes into lush, green areas, with benefits for agriculture, biodiversity, and the broader ecosystem.

Meteorologists weren’t sold. While some acknowledged localized effects, like minor cloud formation due to temperature differentials, experts like Linda Lam from Weather.com said sustained, regional rainstorms were unlikely due to the complex nature of atmospheric dynamics.

Water Crisis and the Case for Desperation

The UAE’s acute water issues form the bedrock of the project’s rationale. The country experiences a paltry 120 millimeters of rainfall annually, and according to a 2015 Associated Press report, its groundwater could be fully depleted within 15 years. Meanwhile, the Gulf states have among the highest water usage rates in the world: around 500 liters per person per day.

Desalination, though critical, is energy-intensive, costly, and environmentally damaging. Alshehi warned of desalination plants pumping concentrated brine back into the Gulf, increasing salinity and harming marine life. His iceberg initiative, he claimed, would be not only cheaper in the long run but eco-friendlier, despite concerns about dragging a 100,000-year-old ice mass across the globe.

He asserted that environmental impact assessments had been conducted, and results suggested minimal disruption to ecosystems,though no independent third-party review was ever published.

Ice, Reimagined: A Greenland Startup Finds the Sweet Spot

While Alshehi’s Antarctic ambitions appear stalled in bureaucratic limbo, a smaller, scrappier company in Greenland has quietly realized a modest version of his vision,not as a humanitarian water source, but as luxury indulgence.

Founded in 2022 by Greenlandic entrepreneurs, Arctic Ice ships ice harvested from Greenland’s fjords to high-end bars and restaurants in Dubai. Their first commercial shipment, around 22 metric tonnes, arrived recently, offering the “cleanest H₂O on Earth” to be shaved into ice cubes for cocktails, ice baths, and facial massages in Dubai’s spas.

The process is artisanal: Using a crane-equipped boat, workers collect naturally calved icebergs from the Nuup Kangerlua fjord near Nuuk. Only the clearest, bubble-free ice, locally known as “black ice,” is selected. These are believed to be over 100,000 years old, having never touched soil or contaminants.

Each chunk is cut with sanitized chainsaws, stored in food-grade insulated crates, and sampled for lab analysis to screen for ancient microorganisms or harmful bacteria. The ice is shipped via refrigerated containers aboard cargo ships already returning empty from Greenland, minimizing additional emissions. The second leg, from Denmark to Dubai, completes the frozen supply chain.

Despite the company’s carbon-neutral commitment, backlash has been fierce. Critics online lambast the concept as “climate dystopia,” arguing that glacial ice should not be commodified, especially given the accelerating melt of the Greenland Ice Sheet. Co-founder Malik V. Rasmussen says some messages have verged on death threats.

Still, Arctic Ice insists it is creating economic opportunity for a financially dependent Greenland, where 55% of the budget is subsidized by Denmark. “We make all our money from fish and tourism,” Rasmussen said. “I’ve always wanted to find something else we can profit from.”

The Fine Line Between Innovation and Spectacle

Both projects,the giant iceberg tow from Antarctica and the boutique glacier cubes from Greenland, highlight a pressing tension: how far will humanity go to secure water, and at what cost?

Alshehi’s vision is bold but fraught with logistical and ethical challenges. Icebergs aren’t endlessly renewable, and towing them across hemispheres feels more sci-fi than sustainable.

Arctic Ice’s venture, meanwhile, has found a controversial niche,combining novelty, luxury, and symbolism. In a time of climate anxiety, it offers an icy illusion of control, frozen fragments of a melting world, crafted into cocktail spheres.

Whether climate solution or spectacle, these ideas raise key questions: Who owns natural ice? Can it be harvested responsibly? And as water scarcity grows, how do we balance local needs with global care?

For now, the UAE’s giant iceberg remains a dream deferred, and Dubai’s cocktails are as cold as ever, just sourced from a little farther north, and in smaller, sparkling doses.

You may also like

'My friend is naming her baby after a fish – she can't see how ugly it is'

Spain captain sends ominous warning to Lionesses ahead of Euro 2025 final

AC/DC fans are only just realising unlikely inspiration behind band's name after 51 years

Tomato plants thrive and grow better with 1 leftover food item they 'love'

England's Hannah Hampton was told not to play football due to health condition